Mail Art to Social Networks: Artistic Scouts Anticipate the Internet

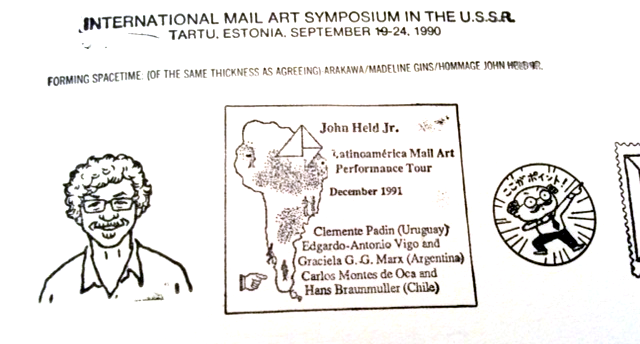

By John Held Jr. USA, 2019.

Previous to the Internet, the cheapest form of communication was provided by the postal system. When it established itself internationally in the mid-19th century, it was a major advancement resulting in a host of new accomplishments ushering in modernity by advancing the formation of firm political boundaries, international trade and treaty, shrinking the world by advancing cheap efficient personal communication among friends both far and wide.

The ways in which we transfer information are constantly updated by the technologies provided us. Before the advent of digitation and the Internet, we were “reduced” to tangible analog communication: books, periodicals, recordings…letters. New technologies are advanced by economics and efficiency. The Internet has prospered by providing us with instantaneous international communication at low cost.

From the beginning, artists have taken advantage of the postal system to forge friendships and share artistic developments. Envelope and stationary decoration occurred from the very introduction of postcards and letters. Not only was art shared, but the ideas behind it, and it is very likely that modernist art movements like Impressionism and Dada were significantly encouraged by mailings between international artists with similar concerns.

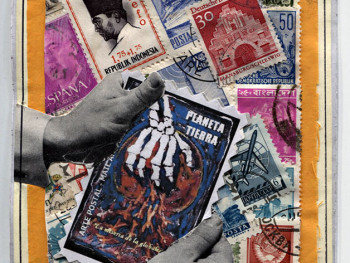

A more contemporary example of international artistic cooperation forged through the postal system is Fluxus, formed in 1962, guided by New York artist George Maciunas, hailing from Lithuania, who became a switchboard for culturally and geographically diverse artists. Macunias encouraged those of similar avant-garde tendencies to interact with one another, linked by personal letter writing and mailed newsletters, spreading collegial news and planning for cooperative projects and performances. It is little wonder that among the activities of the artists were the creation of faux postage stamps, postcards and rubber stamps – all items associated with the post office.

But when we talk of the artistic use of the postal system during this post-war period, our attention turns to Ray Johnson, a student at Black Mountain College, associated with many artists that were searching for a way beyond Abstract Expressionism, including John Cage, Merce Cunningham, Robert Rauschenberg, Cy Twomby, Ruth Asawa, Buckminster Fuller…the list goes on and on. Unlike many of his fellow students and instructors who readied themselves in existing cultural structures, at the end of his schooling, Johnson burnt the majority of his paintings, and bypassed the gallery and museum establishment, sending artistic missives directly to known and unknown persons.

The purity of his art, his craftsmanship, his seeming disregard for critical acclaim, and the generosity of his acts, endeared him to artists, who benefitted as his correspondents. Begun as an unconscious act of private communication with high school friends in the 1940s, becoming a way to introduce himself to the New York graphic arts community in the 1950s, by the 1960s he was encouraging his correspondents to “add and pass” to either a known or unknown third party, extending the postal encounter into a network of correspondents.

It was this simple act of encouraging the participation of other artists to interact with one another through intuition and inclination, which set Johnson apart. A network was established, first within the New York art community, many of whom were associated with Fluxus, spread in the early 1970s by the Canadian art collective General Idea, which began publication of FILE magazine, backed by the generosity of the Canadian Art Council, enabling widespread international dissemination of the journal. General Idea picked up on Johnson right away, adopting him as the poster boy of a new art form…Mail Art.

After the introduction of Johnson’s practice in VILE magazine, and the publication of an article on his postal activities in Rolling Stone magazine, the growth of the new art form spread exponentially. The medium gained a measure of exposure when Marcia Tucker, a curator at the Whitney Museum of American Art, encouraged Johnson to show work from his New York Correspondence School, as his activity had become to be known as early as 1962. In response to this, Johnson issued a call to correspondents to send directly to the Museum, which was gathered by Tucker and pinned to the wall. It became a model for mail art exhibitions, which gained momentum during the decade, with the guidelines, “no fees to enter, all work shown, documentation to participants.”

Previous to the postal activities of Johnson, artists routinely paid fees to enter juried shows, entailing a costly and labor intensive assembling of slides as introduction. Rejection was common, discouraging many. Mail Art democratized art allowing anyone to participate. Mail Art stressed cooperation, not competition. Art became a gift exchanged among friends. Artists became linked across divides of geography, language and culture in a good faith effort to participate in a shared activity for the greater good.

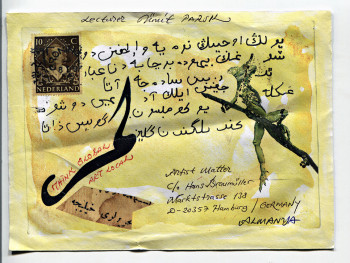

Beginning as a New York insider art activity (Johnson became known as the most famous unknown artist in New York), by the 1980s well organized Mail Art exhibitions (held in libraries, university galleries and other non commercial spaces) were attracting an average of 300 participating artists from 30 countries. In 1986, under the encouragement of Swiss artists, H. R. Fricker and Günther Ruch, A Worldwide Decentralized Mail Art Congress was convened, “wherever two or more Mail artists meet,” to discourse on the medium. At the conclusion of the year, Ruch issued a report listing 80 such meetings in a variety of countries.

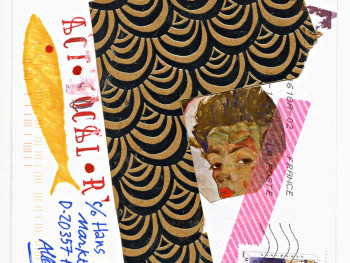

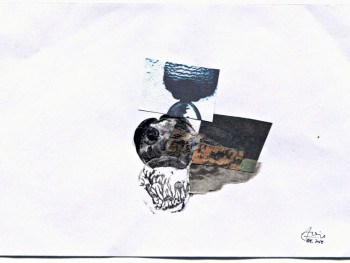

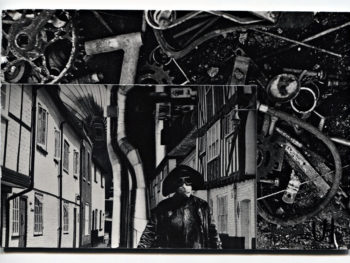

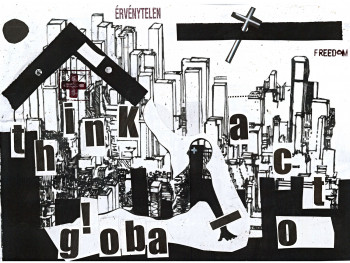

As the 1990s rolled around, Mail Art had become a widespread underground postal based activity serving as an umbrella for a host of marginal artforms including artist books, collage, photocopy, rubber stamps, zines, as well as using established art mediums, such as painting, printmaking and photography, in unconventional manners. Mail Art, was continuing to serve as an important link between Western artists and their counterparts practicing under more rigidly controlled political regimes in the Soviet Union, Eastern Europe and South America, where information on contemporary art was difficult to attain.

In 1995, Ray Johnson passed away…but not the medium he engendered. A substantial Mail Art exhibition held at the Palace of Fine Arts in Havana, Cuba, attracted some 600 artists from 40 countries. It was also the year that a book on the subject was first published by a University Press. But along with the seeming surfacing of the medium, a hidden giant lurked. The Internet was gaining momentum, rearing its head in the early part of the decade, and by 1995, becoming an approachable medium for many, including the Mail Art community, which along with everyone else, began “e-mailing,” and gathering in “chat groups” across international boundaries. Somewhat later, zines gave way to blogs; easier and cheaper to produce with increased circulation at no additional expense.

But let us not forget, previous to the Internet, artists had anticipated participation in an international community linked by communication, encouraging creativity and friendship across borders, serving as a model for our current communication situation. The postal system is no longer the cheapest most efficient communication medium. The Internet has been a revelation and a revolution, which we are still dealing with. The Internet has connected the world in a way unimaginable, yet Mail Artists have made the jump seamlessly. There is a reason so many veteran Mail Artists are currently active on Facebook. It is a familiar pursuit, dressed in new clothing.

Once an underground art activity, the accessibility of information on Mail Art available through the Internet has encouraged unprecedented participation. More people are now participating in Mail Art more then ever before. The digital nature of the Internet encourages one to take hand to paper, passed to others on a schedule of ones choosing. It remains a private form of communication, leaving a tangible object in its wake.

But Mail Art has changed. From a movement espousing global cultural solidarity, it has become a medium, where craft becomes upmost. Mail Art doesn’t seem avant-garde anymore. The scouts went out, surveyed the landscape, tuned their antennas to the future, and returned with the message that a more culturally connected world was coming. But that was the whole point: to democratize, decommodify and decentralize art. All of which the Internet has accomplished.

Written in conjunction with the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art exhibition, “snap+share: transmitting photographs from mail art to social networks” opening March 29 (runs through August).